Over the last year, I’ve been habitually checking out the pandemic charts on Our World in Data on a daily basis. What started out as an anxious obsession with an unknown threat has become an unusual source of calm and perspective. Most days look exactly like the day before, but sometimes a remarkable trend will suddenly leap out at you. This is particularly true during inflection points of the pandemic, like when a new variant emerges or a new vaccine is announced. Well, we’re going through one of those inflection points now, so let me share with you five trends that have been standing out to me recently.

The global story: Vaccinations up, deaths down (for now)

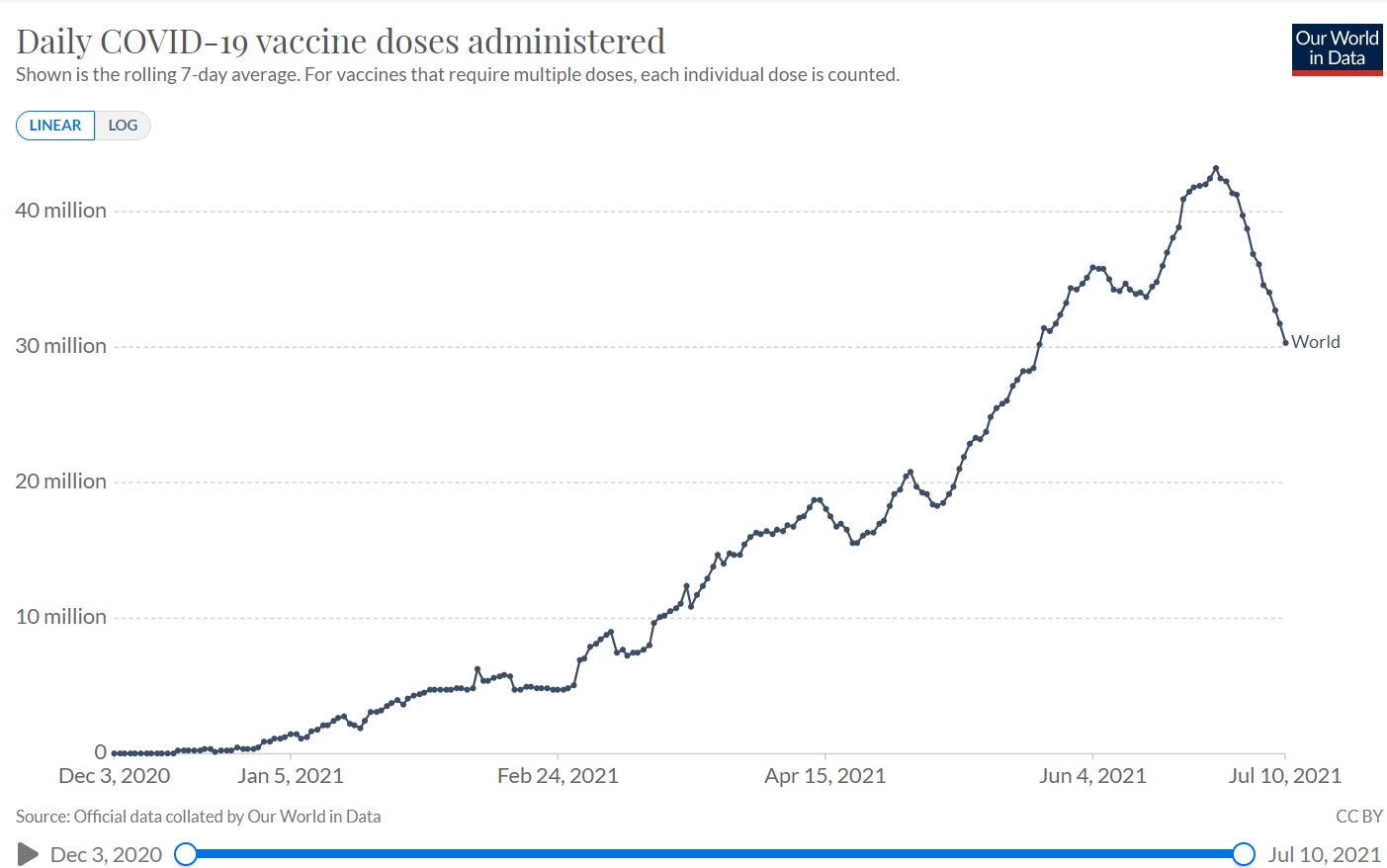

This isn’t the most surprising story, but it’s definitely the most important. As vaccine producers have ramped up capacity, the rate of vaccination has accelerated dramatically. If the trend that held from the middle of March until the end of June persisted, by the end of October we’d have been putting vaccines in the arms of 1% of the global population every single day. However, last week’s precipitous drop in new vaccinations places a troubling asterisk over this. Most of the previous acceleration had taken place in the efficient, centralised states of Europe, China, East Asia, and North America. India is giving us our first glimpse of what a slow rollout might look like, and COVAX will need every dollar it can get to fund and co-ordinate the rollout to poorer countrieDespite the challenges, we’re already seeing dividends from the rollout. Daily COVID mortality has fallen by almost half since the beginning of May. Global GDP growth is expected to be 3.2%, better than the average for the last 10 years. The game is far from over, but it’s no small feat that there has yet to be a major sovereign debt crisis associated with the coronavirus pandemic. In America, the country with the worst epidemiological response but the best economic response, the rebound is even more dramatic, with poverty actually falling as a result of the various stimulus packages.

The road ahead is rocky, with fiscal adjustments and an arduous public health effort still to come. The uptick in cases associated with the delta variant is also troubling. But for now at least, our efforts are bearing fruit.

China: Putting the West to shame

For most of the last few decades, China could be thought of as having taken a cheap shortcut to superpower status. Its growth rate was high, but it was largely catch-up growth on a par with other developing nations; its population was gargantuan, but much of that population was poor and oppressed. They never had the kind of technologically driven “Schumpeterian” growth that gives the world such faith in the U.S. dollar as the global reserve currency. Even as the juggernaut persisted inexorably toward greatness, many suspected that it could sputter out at any moment.

No more.

If the dominant lesson of global development in the late 20th century was that the East was capable of emulating the success West, in the 21st century we’re learning that the East can do it better. This was a tolerable notion when it was true only of the insular, liberal democratic islands and peninsulas of Japan and South Korea. If their trains were faster and their rents were lower, then so be it – they could serve as an example to the rest of us. It is entirely possible to be impressed without feeling threatened.

But China is not just impressive. China is ambitious. You may have heard of the massive infrastructure investments the Chinese government has been making in Africa. Bridges and roads and sports stadiums, all built by Chinese construction teams. What you may not be aware of is that Europe has been engaged in a similar, much more half-hearted, pathetic effort at ingratiating itself into the hearts and minds of the countries it used to colonize. It hasn’t worked. This Chinese supremacy plays out in other fields, too. Since 1970, 43 new $100 billion companies have been founded; ten of those were in China, one was in Europe (the rest were in America). While Ireland – the economic pride and joy of the EU – bumbles and flails its way through a decade long housing crisis, China is consuming more concrete every three years than America did in the entire 20th century. I could go on1.

The pandemic has made these disparities of dynamism even more evident. Rounding to the nearest 10,000, America has seen 610,000 deaths from coronavirus, Europe has seen 740,000, and China has seen zero (rounding down from 4,636). As of June, China has surpassed Europe in the number of vaccine doses administered per capita, and by the end of July it will have surpassed America. In absolute terms, China has administered 1.35 billion vaccine doses to a country of 1.4 billion people.

This should read as unambiguously good news, but the foreign policy community is primed to perceive almost any news from China as a threat. Over at Chartbook, Adam Tooze has diligently documented Biden’s “repgrogramming” as a China hawk. On the campaign trail in 2020, Biden was dismissive of even the notion that China should occupy a prominent place on the foreign policy agenda: “They’re not bad folks, folks. But guess what? They’re not competition for us.” A year later, Biden’s first speech at the state department is worth quoting extensively:

American leadership must meet this new moment of advancing authoritarianism, including the growing ambitions of China to rival the United States … we’ll also take on directly the challenges posed by our prosperity, security, and democratic values by our most serious competitor, China. … we are ready to work with Beijing when it’s in America’s interest to do so. We will compete from a position of strength by building back better at home, working with our allies and partners, renewing our role in international institutions, and reclaiming our credibility and moral authority, much of which has been lost."

Europe, meanwhile, has been imposing sanctions against Chinese officials as punishment for their treatment of Uighur minorities in Xinjiang. This has already escalated into a tit-for-tat economic conflict which has resulted in the EU-Chinese “Comprehensive Agreement on Investment” (“CAI”) being put in deep freeze.

Some of this hostility is firmly rooted in policy conflict. The European Union, for instance, has a self-conception as a bastion of human rights and equality, and this makes Chinese treatment of the Xinjiang Uighur population particularly problematic in diplomatic negotiations. But it’s hard not to see the role of sheer status competition in inflaming these tensions. A world where China is capable of being not just biggest, but also best, is one in which Europe and America no longer have that claim.

America: The government and the people

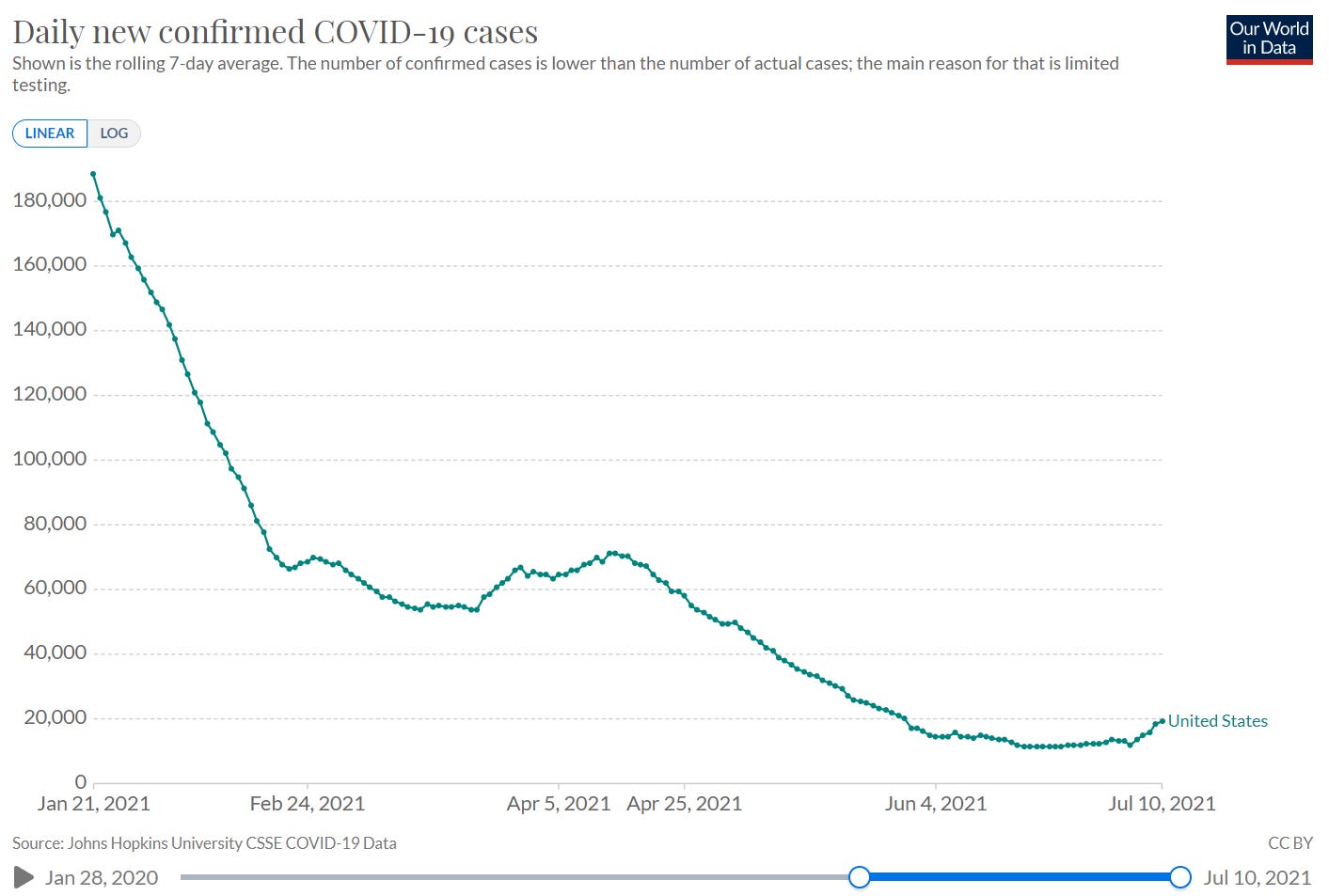

Throughout 2020, it was clear that governmental failings were at the heart of the American coronavirus crisis. The Republican party was tearing itself apart over its commitment to austerity, and Donald Trump was more interested in demonizing the Black Lives Matter movement than in leading his party. Meanwhile, the people were pulling more than their own weight. Parts of America had some of the strictest lockdowns in the world, with schools staying closed throughout 2020.

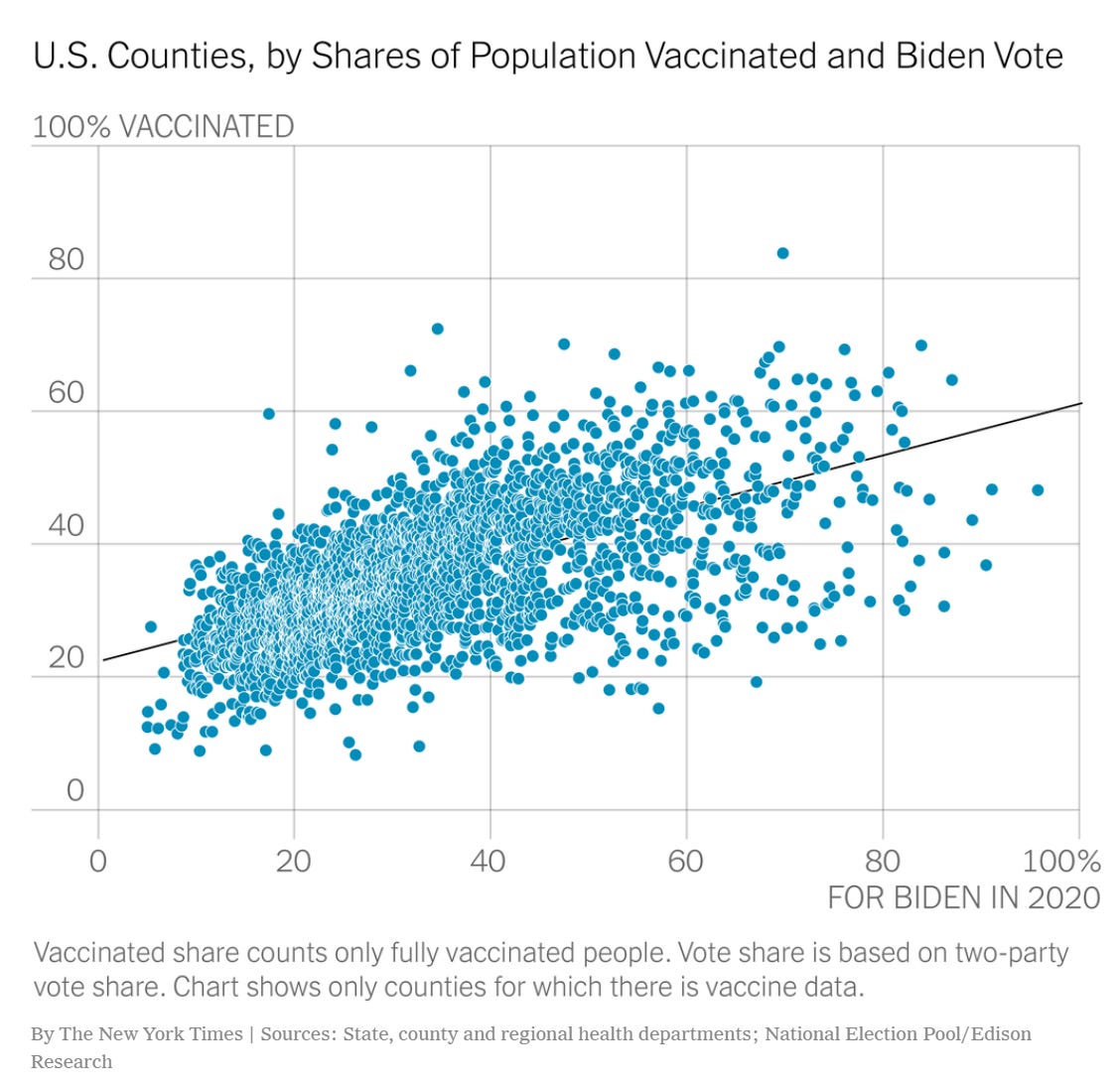

When Biden took over at the beginning of this year, things appeared to take a turn for the better. In absolute terms, America had one of the fastest vaccination rates in the world, and his economic stimulus packages made lockdowns more tolerable where they persisted. But the forces which brought Donald Trump to power are still in play. Widespread suspicion of public institutions has left America with levels of vaccine hesitancy unparalleled in the developed world. As the delta variant begins to make its presence felt across the Atlantic, COVID deaths are beginning to take on a partisan skew. Going from a county with a Biden vote share of 20% to one with 80% doubles the expected vaccination rate of that county.

It’s not yet clear how catastrophic the consequences of this hesitancy will be. It may be that over time most American communities reach herd immunity by hook or by crook. Those who are not vaccinated may catch the virus and achieve some degree of immunity that way. Such a scenario would not be pleasant – many who catch the virus will die, and many others will suffer unnecessarily – but it is not the worst case scenario. As we’ve all been hearing lately, the real risk of low vaccination rates is not further deaths, but further mutations. If America can’t reach herd immunity quickly, it will become a breeding ground for more virulent, vaccine resistant strains, and there will be little that good government can do to help.

Africa and South America: A mystery to me

The big question that I’m left with at this point in the pandemic is this: Why are there so many coronavirus cases in South America and so few in Africa? South America has a lot of weak governments who are ill placed to respond to a pandemic, but so does Africa. Africa is very warm, which seems to help, but so is South America. This is obviously a very crude question, but it’s not one that I’ve seen a satisfying answer to.

The UK: As many coronavirus cases as the entire European Union

The Delta variant which is spreading like wildfire through the British population has yet to cause a dramatic increase in deaths, but it definitely threatens to. The London Underground is packed once again, and it is too soon to say whether the national response will be enough to slow down the spread. Furthermore, the risks of hyper-contagious strains are compounding: the more contagious a variant, the more opportunities it will have mutate into something more deadly to the population it infects.

This story is all the more tragic given the way it complicates the genuine achievements of British society during this pandemic. A month ago, the prevailing narrative was that Britain had designed an effective vaccine in record time, were among the first to begin their rollout, and are now on a par with Israel for the speed of their rollout. For a time, it looked like Boris Johnson would be remembered not for the tragic death toll of 2020, but the miraculous recovery of 2021. Now all that has been thrown into question.

As it is for Britain, so is it for the world. For all the miraculous progress that has been made in recent months, the battle is still ours to lose. 3.5 billion doses is a lot, but it’s not close to where we need to be. Africa, a continent of 1.2 billion people, has administered only 55 million vaccines, about the same amount as the country of Spain. Such immunological lacunae are breeding grounds for new variants. So far, Africa’s aforementioned epidemiological good luck has protected it from the mass death we have seen elsewhere, but this won’t hold forever. India, too, used to have an unusually low case load.

Conclusion: Everything to Play For

Nothing is inevitable. Humanity has achieved the unimaginable time and time again in the past year; we can do it again in the next year. But it will mean taking the problem seriously. We can’t keep wasting time futzing around with intellectual property rights. We need to implement solutions that work: faster vaccine approval, fractional dosing, dose spacing, an end to export bans, a massive increase in COVAX funding, and a concerted global attempt to co-ordinate supply chains.

This in turn will depend on our collective capacity to care about this pandemic once we can no longer see it. Until now, it has made perfect sense for the Irish media to cover the pandemic from an Irish perspective. But as we rapidly approach herd immunity (I think we’ll get to 100 doses per 100 people by the end of next week), we are at risk of coming under the illusion that we are safe. But the vaccines only protect us against the variants that already exist. If further mutations bring us back to square one, it will be because we have forgotten John Donne’s eternal wisdom:

No man is an island entire of itself; every man

is a piece of the continent, a part of the main …

any man's death diminishes me,

because I am involved in mankind.

And therefore never send to know for whom

the bell tolls; it tolls for thee.

.

Further Reading

Our World in Data is quickly placing itself on a par with Wikipedia as an indispensable online information resource. Their pandemic data explorer was my main source for this post.

YouTube lecture series on China

*High speed rail, green energy, and pollution reductions, all also to stand make China a world leader on the environmental front.